I was always the kid who begged my teacher not to assign me to a group project but to let me do an individual one. When I did end up with a group, one of three things happened: 1) they ignored me; 2) they made fun of me for my odd appearance and behavior; 3) they had me do all the work.

As an adult I was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, now part of the autism spectrum, and it answered the questions I had about why I never fit in, why it was so hard for me to make friends, and why I always seemed to get into trouble no matter how hard I tried to follow the rules. At the time I edited MultiCultural Review from my home office, keeping in contact with my supervisor, writers, and copyeditor via phone and email. I’d also harbored dreams of writing fiction for teens and adults but avoided writing directly about my own experiences growing up because they were too painful. My autism spectrum diagnosis forced me to face my past and inspired me to write about it for young people who may be going through the same things I experienced, so they would know they weren’t alone. Currently, one in 68 children is diagnosed with autism, though underdiagnosis is still more common in girls and women.

As an adult I was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, now part of the autism spectrum, and it answered the questions I had about why I never fit in, why it was so hard for me to make friends, and why I always seemed to get into trouble no matter how hard I tried to follow the rules. At the time I edited MultiCultural Review from my home office, keeping in contact with my supervisor, writers, and copyeditor via phone and email. I’d also harbored dreams of writing fiction for teens and adults but avoided writing directly about my own experiences growing up because they were too painful. My autism spectrum diagnosis forced me to face my past and inspired me to write about it for young people who may be going through the same things I experienced, so they would know they weren’t alone. Currently, one in 68 children is diagnosed with autism, though underdiagnosis is still more common in girls and women.

My novel Rogue, featuring a young teenage girl with undiagnosed Asperger’s and an X-Men obsession in search of a friend and her own special power, came out in 2013, and I am pleased that it gave solace and hope to kids like me. Five years later, Rogue is out of print and I am planning to self-publish a new edition in paperback and e-book at the beginning of 2019. Rogue is also the last book I wrote that has sold to a publisher.

Not including picture books and projects that died out at early stages, write-for-hires and translations (because fascination with languages and the ability to learn them is one of my special powers), I’m now starting my sixth book-length project since Rogue. As I see how publishing has changed over the years, I’m coming to see self-publishing — the individual rather than the group project — as an option for my new work. I wish this weren’t the case. Several of my new books feature an #ownvoices autistic protagonist, and I know that, were these books eligible for purchase in schools and libraries (which self-published books generally are not), they would offer insight and inspiration to teen readers on the spectrum while showing neurotypical readers the value of an autistic perspective.

Not including picture books and projects that died out at early stages, write-for-hires and translations (because fascination with languages and the ability to learn them is one of my special powers), I’m now starting my sixth book-length project since Rogue. As I see how publishing has changed over the years, I’m coming to see self-publishing — the individual rather than the group project — as an option for my new work. I wish this weren’t the case. Several of my new books feature an #ownvoices autistic protagonist, and I know that, were these books eligible for purchase in schools and libraries (which self-published books generally are not), they would offer insight and inspiration to teen readers on the spectrum while showing neurotypical readers the value of an autistic perspective.

Still, I am proud to have been a pioneer. I cheer the successes of new autistic children’s authors — many of them women, queer, and IPOC — who have emerged in the past several years, as well as those who are signing their first contracts now. I think there are ways publishing can change to be more friendly to neurodiverse authors, and I believe that the industry can and should accommodate rather than ask us to do all the changing. Because we can’t. We are who we are, and the anxiety of being forced to act differently is intense and disruptive of already fragile lives and relationships. Many of us will fail despite our best efforts.

In the spirit of being positive and proactive, I’d like to suggest ways that editors and sales/marketing staff can help autistic authors to maintain successful careers.

One of the most difficult things for me to deal with as an autistic author is the dominant communication style of the industry. Everyone appears friendly. Everyone smiles. I interpreted that as a sign that they liked me, approved of whatever I was doing, and wanted me to hang around. I cannot “read between the lines.” I need to be told what is appropriate behavior in person and on social media — and the reason why. I may need to be told multiple times. As I’ve explained to students in school visits, having autism is similar to having a learning disability like dyslexia, except it’s in social communication rather than reading. And while children’s publishing is female-dominated, autistic women often follow patterns of interaction and communication more often identified as male or outside traditional gender categories altogether. When I was growing up, my cruelest tormentors were usually other girls, whose words and actions seemed to contradict each other, making it almost impossible for me to understand them.

Related to that is the way editors often interact with authors during the revision process. An editor who feels strongly that an aspect of plot or character needs to be changed may say, “You should think about changing this.” At this point, I would respond “I thought about changing this but decided in the end not to do it.” In other words, this kind of suggestive language doesn’t work for me. Instead, the editor should say, “You need to change this right away!!” And add a reason that appeals to the rational, legalistic part of my brain, such as, “If you don’t make the change, many school districts won’t be able to buy the book, and you won’t reach the audience you’re trying to reach.”

The emphasis on self-promotion is another way that autistic authors are disadvantaged, and where changes on the publisher level can build skills and success. When my book came out, I received a one-page sheet on how to organize a bookstore signing. I know it’s tough for authors to go into a bookstore and chat up the buyers to gain support, but for me, it’s more than social anxiety. My efforts have been, in a word, counterproductive. Many autistic people need social scripts, and this is one way that publicists can work with writers on the spectrum. Yes, it takes time and and the dedication of additional resources. However, if publishers want to invest in an author’s career, one of the things they can do is give their own voices autistic authors the skills to self-advocate for their work effectively. A large publisher should have at least one publicist on staff with the ability to work with neurodiverse authors — ideally, a publicist who is neurodiverse as well.

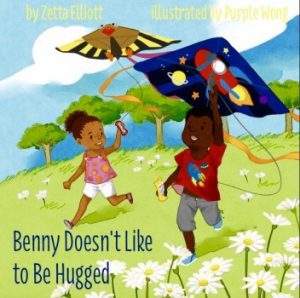

Benny Doesn’t Like to Be Hugged explores through poetry and image a young girl’s friendship with autistic Benny. I was a consultant for this critically acclaimed self-published book.

I stand ready to help authors and publisher with additional thoughts on this topic, but would also like to make one other point for #kidlitwomen month. People choose self-publishing for a variety of reasons, and it shouldn’t be a ticket to instant exclusion and pariah-dom. If I do choose this path — or it is chosen for me — I don’t want to say good-bye to people I considered colleagues and friends. You have enriched my experience as a writer, and I hope I have enriched yours. I would also like you to consider for inclusion on panels other marginalized authors who have chosen self-publishing. For years, Zetta Elliott has inspired me with her writing, her vision, and her perspective. She would be a brilliant addition to any panel or conference serious about including women of color. In a piece for School Library Journal, she writes:

Last year a white Facebook “friend” suggested that my decision to self-publish was analogous to Blacks in the civil rights era choosing to dine in their segregated neighborhood instead of integrating Jim Crow lunch counters in the South. In her mind, self-publishing is a cowardly form of surrender; to be truly noble (and, therefore, deserving of publication) I ought to patiently insist upon my right to sit alongside white authors regardless of the hostility, rejection, and disdain I regularly encounter….

It frustrates me that most people seem comfortable with the reform of the existing system rather than its transformation. The idea of trying something new seems positively terrifying, and those of us proposing viable alternatives are generally shut out of the diversity discussion.

My Lego town, Little Brick Township, is a school visit favorite. It combines kits and original creations in a realistic style drawn from historic buildings.

This needs to change, and brave people genuinely committed to diversity and justice are the people who should take the first steps to change it. From my perspective as an autistic author with three traditionally published books for tweens and teens, now self-publishing a new edition of one of them and considering going it alone for my newest work, I ask you to do two things. Embrace authors whose work you like and who have chosen other paths besides the traditional one. And work to make the publishing industry more inclusive and friendly to disabled and neurodiverse authors so that our voices become part of the canon and inspire those coming along behind us.